|

Mycoplasma haemolama

formerly known as

EPE (Eperythrozoonosis) in Camelids

|

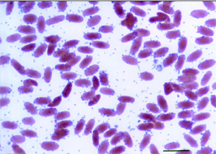

Peripheral blood smear from a

4-day-old cria illustrating the light microscopic appearance of

Mycoplasma haemolamae and massive erythrocyte parasitemia.

|

The Infection Formerly Known as Eperythrozoonosis in Camelids:

New information and New Test, Susan J. Tornquist, DVM, PhD, Dip. ACVP

College of Veterinary Medicine, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, 97331

An Eperythrozooon species affecting camelids has recently been reclassified as Mycoplasma haemolama based on its 16s rRNA sequence.

1. It is most closely related to M. wenyonii, which affects cattle, then to M. haemosuis (formerly Eperythrozoon suis), which affects pigs and somewhat less to M. haemominutum (formerly one of the Hemobartonella felis isolates) which affects cats. M. haemolama was first described in 1990.

2,3. It is associated with mild to marked anemia and rarely, death, in stressed, immune-suppressed, and debilitated camelids. It has also been identified in low numbers in apparently healthy camelids. Some camelid herds with high rates of M. haemolama based on blood smear examination have experienced acute collapse, chronic weight loss, depression, and lethargy. These clinical signs, and

the presence of the hemoparasite on blood smears are sometimes associated with shipping or movement of camelids from one premise to another.

The mode of transmission is not known and little had been reported about prevalence, the effects of treatment on the carrier state, and the pathogenesis of infection and disease with this hemoparasite. This has led to confusion among veterinarians and owners as to whether all infected camelids and their herdmates should be treated and how finding the hemoparasite on blood smears from clinically-healthy camelids should affect pre-purchase exams and shipping of animals.

Grants from the Morris Animal Foundation and the Alpaca Research Foundation allowed us to carry out two projects that were designed to develop a sensitive and specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay to detect the presence of M. haemolama even at low levels of parasitemia. We then used the assay to study the kinetics of parasitemia, response to antibiotic treatment, and presence of a carrier state that may recrudesce to a clinical level with stress. The long-term goal of these projects is to study the transmission and risk factors of M. haemolama infection in camelids.

A PCR-based assay to amplify the 16S ribosomal RNA gene of M. haemolama was developed using primers based on GenBank sequence accession AF306346 and blood from a naturally-infected alpaca. Specificity was shown by failure of these primers to amplify related Mycoplasma species. Parasitemia was detected in llamas and alpacas from a variety of geographic location using the assay. The detection limit is estimated to be 1 organism in 3.8 x 10 9 to 7.7 x 10 9 RBCs.

Since the hemotropic mycoplasmas have not been successfully produced in vitro, a splenectomized alpaca infected with M. haemolama provided blood for experimental infection of 8 other alpacas. All developed parasitemia detectable by PCR at least 2 days before organisms were seen on blood smears. Four of the infected alpacas were treated with a commonly-used tetracycline regime and four were not. All animals were monitored for over 6 months by physical examination, body temperature, PCV, total protein,

blood smear examination, and PCR for M. haemolama in blood. At the end of 6 months, the animals were given intravenous examethasone at an immunosuppressive dose to simulate the effects of stress or immune suppression and parameters as described above were measured.

4. The results of this study will be published. Overall, the results show that:

- Parasitemia is not cleared by the standard tetracycline regime used in camelids

- Once infected, many camelids may become chronic carriers

- The PCR assay is more sensitive than blood smear exam for diagnosis of M. haemolama

The PCR assay is now available for $19 through submission of whole, EDTA-anti-coagulated blood to the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Oregon State University. For questions about the assay, contact Dr. Sue Tornquist at (541) 737-6943 or Susan.Tornquist@oregonstate.edu

References: 1. Messick JB, Walker PG, Raphael W, Berent L, Shi X. 'Candidatus mycoplasma haemodidelphidis' sp. nov., 'Candidatus mycoplasma haemolamae' sp. nov. and Mycoplasma haemocanic comb. nov., haemotrophic parasites from a naturally infected opossum (Didelphis virginiana), alpaca (Lama pacos) and dog (Canis familiaris): phyogenetic and secondary

structural relatedness of their 16S rRNA genes to other mycoplasmas. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52: 693-698, 2002.

2. McLaughlin BG, Evans CN, McLaughlin PS, Johnson LW, Smith AR, Zachary JF. An Eperythrozoon-like parasite in llamas, J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990 197: 1170-1175, 1990.

3. Reagan WJ, Garry F, Thrall MA, Colgan S, Hutchison J, Weiser MG. The clinicopathologic, light, and scanning electron microscopic features of eperythrozoonosis in four naturally-infected llamas. Vet Pathol, 27 426-431, 1990.

4. Tornquist SJ, Boeder LJ, Parker JE, Cebra CK, Messick J. Use of a polymerase chain reaction assay to study the carrier state in

infection with camelid Mycoplasma haemolama, formerly Eperythrozoon spp infection in camelids. (Abs) Vet Path 39: 616, 2002.

Epe - now

reclassified as Mycoplasma haemolama

"What's an epe -- epe-erythr-- What's an epe?

"It's a mouthful, isn't it? An eperythrozooan is a little bacterium that affects the red blood cells. It actually sits on the red blood cells and the immune system sees that as a problem and figures it has to take out the red blood cells and destroy them. It can lead to severe anemia or mild or moderate anemia particularly in animals that are stressed or immune compromised.

"I don't want to give the impression that this disease is killing alpacas right and left. The organism probably does not kill animals - at least by itself. We see it more often as complicating factor in other diseases, and in that sense it's worth figuring out more about it and how to prevent it."

Dr. Tornquist says that since it was first described in camelids in 1990, we still don't know much more about camelid perythrozoonosis. We still don't know how it's transmitted.

Tetracycline is the treatment of choice, but what is unclear is if the tetracycline actually makes the organism go away, or if it doesn't just suppress the disease to undetectable levels. Then, if an animal carrying low levels of the organism gets stressed by shipping or by some other disease, the eperythrozoons can start multiplying again.

And it is difficult to study a disease if you can't detect it.

"The standard way you would diagnose eperythrozoonosis is take blood, make a blood smear and look for it. But actually it's a little tiny organism and it does fall off the red blood cells if the blood sits on the slide for a while, and it can look like precipitate in the background. So definitely if you have low numbers of it, it can be hard to diagnose with the standard test."

So Dr. Tornquist and her colleagues came up with a better test - a PCR-based assay. What's a PCR?

"PCR stands for preliminary chain reaction. It's a way of amplifying the DNA from a sample. So if you have something that's present in a really low level in a sample, you amplify it greatly, then you can detect it that way."

She explains that for each thing you want to look for, you have to develop a specific test. Dr. Tornquist's team developed a PCR-based test specifically for camelid eperythrozoonosis.

"Then we actually infected eight alpacas, and we've been using the test to monitor how soon after infection do they get the disease. We give tetracycline to half of them and not to the other half. A healthy animal usually fights the eperythrozoonosis off on its own in a couple days.

"Now we're monitoring them. We're going to be doing this for about six months. At the end of that time we're going to see if there's a

difference in the two groups as to whether one group still has the organism and the other doesn't, or whether it's wiped out in both, or just exactly how effective is the treatment in absolutely getting rid of the organism.

"The first step was coming up with this more sensitive diagnostic test. "So that's what we're doing with the current project then, hopefully, figure out how it's transmitted."

Is it transmitted from mother to cria?

"We haven't shown that for sure but we've diagnosed it in cria as young as a couple days, to me that's pretty good evidence that they can be infected in utero."

Was the mother symptomatic?

"No. With the better diagnostic test we may pick some more of these that are positive.

"The other question that comes up a lot is: if a veterinarian does a health test on an alpaca and finds that it has low level eperythrozoonosis but otherwise seems healthy, should you test or should you treat all the other animals in the herd?

Usually you don't find eperythrozoonosis in the other animals but it may be there in a low level. And that's where our PCR

assay could be helpful in detecting. And then: is it okay to sell an animal that has eperythrozoonosis and say that it's a healthy animal?"

The alpacas that you infected for the test, did they fight it off?

"We have one - it's been two months now - we continue to pick it up in him."

Was he treated or untreated?

"The one having the recurrences was treated with antibiotics."

Is there any geographical preference for this bug?

"It's been described pretty much everywhere."

Is it seasonal?

"The seasonality question is interesting. Here in Oregon - this is not based on study, just on observation - we tend to see it more in the late summer and fall, not so much in winter. So that sort of fits with maybe there's an insect vector, but that hasn't been proven."

Can it spread through mating?

"Possible. We can't rule that out. But due to the nature of the organism that it's found in blood and no where else - it makes it a little less likely that that's actually the case."

Once the alpaca has recovered on its own once, is it immune?

"We don't know that either. But they do make antibodies, which is part of the immune response. We don't know for sure that antibody is protective. And that's another thing that would be good to look at. I don't know if this disease is enough of a problem that we would ever want to develop a vaccine but that's the kind of question that's important when you're developing a vaccine."

If we treat the alpacas for it and they still have it, are we making supergerms?

"In most of them that are treated, it's never a problem again. Clearly the treatment doesn't work 100% in all cases."

What's an owner to do?

"At this point as an owner I would say don't worry about it too much. If you have animals that aren't doing right, losing weight, seeming sick, you would naturally probably have a vet check them out.

"We haven't started doing the new PCR-based test as a regular diagnostic test - which means we don't charge money for it. Obviously, eventually, we'll have to do that because it's not cheap to run, but we're still at that point where we're interested in testing strains from different parts of the country, and so it's actually helpful to get samples from animals in different places. So at this point if someone wanted the PCR assay run, they could contact me and we could set up sending in some blood and testing it. Eventually we're going to have to charge for that, but for now it's still part of making sure we've got a really really good test.

"Having been at both ends - in practice and wishing I had all the answers, then being in research and realizing how long it can take to get anything done - I know it's frustrating for the veterinarians and for the owners. It just takes time, but eventually, if you keep working at it, you get it. Eventually."

- April 2002"

10-20-04

Derek Foster, DVM

Colorado State University

Department of Clinical Sciences

Eperythrozoon

or Mycoplasma haemolamae: New Name for an Old Problem

One

beautiful Colorado evening, you arrive home to find Bonnie, one of your

favorite alpacas, weak, down, and breathing rapidly. A quick exam by your

veterinarian reveals that she is also pale and has a high heart rate,

which also describes you at this point. Some brief blood tests show that

Bonnie is anemic – too few red blood cells – which helps explain her

current signs of illness. Upon microscopic examination of Bonnies’ blood,

your veterinarian announces, “Bonnie has Mycoplasma haemolamae.”

To

which, you (and most of the camelid industry and veterinary profession)

respond, “Huh? What’s that?”

Recently, the red blood cell parasite Eperythrozoon (commonly know

as “Epe”) was renamed Mycoplasma haemolamae based on the results of

genetic studies done on the organism. This change in name is just that, a

name change; it does not reflect any change in our understanding of the

biology of this organism and the disease it causes. If you have had to

deal with Epe in your alpacas, you know that we in the veterinary

profession still have a great deal to learn about this organism, but this

article will summarize what we currently do understand.

What is it?

Mycoplasma haemolamae

is a small bacterium that lives on the red blood cells of camelids, and

was first reported during the early nineties in Colorado and Illinois in a

few sick or immunosuppressed llamas and alpacas. Since its discovery,

Mycoplasma haemolamae has been found throughout the United States.

Similar organisms are seen in pigs, cattle, dogs, cats, and many other

species.

How common is it?

Mycoplasma haemolamae

is found throughout the country and in the majority of camelids in

Colorado. Studies have shown that 25% of camelids nationwide have been

infected, but up to 80% of camelids in and around Colorado are positive.

What does it do?

In the majority of infected alpacas, Mycoplasma haemolamae causes

no disease at all. Chances are that you may have an infected animal and

do not know it. The immune system of some camelids will effectively fight

off the infection and rid the bloodstream of the organism. Other animals’

immune systems will not completely eliminate the organism, but will keep

it at such a low level that it does not cause disease. These

“carrier” animals are the most likely source of infection for other

camelids.

In a

few animals, the immune system is unable to effectively fight the

infection, and the organism destroys red blood cells, causing anemia.

When the immune system fails to fight the parasite, the animal will begin

to show signs of the disease. These signs can appear as either acute or

chronic disease. The signs of acute disease include sudden weakness and

inability to rise, while chronic problems may appear as lethargy, weight

loss, or decreased fertility. In animals that show any of these signs of

disease, there is often an underlying problem that prevents the immune

system from effectively fighting off Mycoplasma haemolamae. These

underlying problems may include pneumonia, ulcers, or even moving the

animal to a new location. Immunosuppression could be caused by a recent

or chronic infectious disease. Non-specific stress such as altered

environment, changes in social status, changes in feed or water source,

increased breeding use for males, or recent transportation can also be

underlying causes of immunosuppression. Unfortunately, it is often

difficult to identify the fundamental cause of immunosuppression as the

initiating event may already have resolved.

How is it spread?

Although other species of animals can carry similar organisms,

Mycoplasma haemolamae appears to only infect alpacas and other

camelids. Transmission of the organism from one animal to another is not

completely understood, but believed to be spread only through contact with

an infected animal’s blood.

Infected “carriers” most commonly do not show clinical signs, but may

transmit the parasite through biting insects such as lice, mites, flies,

or mosquitoes, reused needles, or blood transfusions.

How do we treat it?

In animals with anemia from Mycoplasma haemolamae, treatment with

oxytetracycline can control the infection and allow the red blood cell

count to return to normal. Unfortunately, oxytetracycline is ineffective

in completely eliminating the organism from these animals, so they may

become carriers or may have a relapse if another stressful event occurs.

Currently, no medications have proven effective at eliminating the

organism from “carrier” animals.

Can we prevent it?

Because of the widespread nature of infection, complete prevention is

difficult. To decrease the spread, you should properly control insects

including lice, mites, and biting flies. A new needle should be used for

each animal when treating or vaccinating your herd. Preventing other

diseases through proper vaccination, nutrition, and parasite control may

help prevent severe disease from Mycoplasma haemolamae. Prevention

is best accomplished through routine veterinary care and proper

husbandry.

So

in Bonnies’ case, a round of oxytetracycline effectively returned her to

good health. As she had just returned from a show, it was assumed that

transporting her was the underlying stressor that initiated the acute

disease. Although she could have a relapse, Bonnie should go on to have a

normal, healthy life.

10-1-2004

EPERYTHROZOONOSIS IN LLAMAS AND ALPACAS

Sharon Heisler, Veterinary Student

David E Anderson, DVM, MS, DACVS

Ohio State University

Eperythrozoonosis is an organism that infects the red blood

cells. Their presence may trick the body's immune system into

thinking that these cells are foreign thus causing the immune system to

destroy the cells. The destruction of red blood cells may lead to

life-threatening anemia.

This organism has recently been renamed Mycoplasma haemolama. The

transmission of the organism is via biting insects. Infection with

eperythrozoonosis is found worldwide, throughout the year, and in many

species, including swine, sheep, cattle, mule deer, elk, and goats.

Clinical signs observed are often inappetance, wasting, and occasionally

fever. Upon further examination one may notice pale gums, indicating

anemia, or even a yellow hue to the skin representing jaundice.

Asymptotic carriers, those that are infected but showing no sign of

disease, are often a factor in maintenance of the organism within a herd.

They go without treatment and therefore are infectious when bitten by an

insect and that insect continues to feed off other animals in the herd

infecting them in the process.

Eperythrozoonosis does not have to be the primary disease; in fact it is

often secondary to other clinical manifestation. The most common

association is JLIDS (Juvenile Llama Immunodeficiency Syndrome), severe

intestinal parasite burden, and overwhelming stress. These cases have a

more severe clinical presentation and may suffer repeated infections.

Examination of the blood under a microscope may or may not find the

organism on the red blood cell. If present, this observation makes a

diagnosis of eperythrozoonosis. Blood work is indicated to evaluate the

animal to determine if anemia is present and if a blood transfusion is

warranted. There are serologic tests available for eperythrozoonosis, but

interpretation is difficult. Recently, Dr. Susan Tournquist at Oregon

State

University developed a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test for Mycoplasma

haemolama. This test should be more accurate and improve our ability to

diagnose this infection and perhaps identify carriers of the disease.

When anemia and clinical disease are associated with M. haemolama

infection, treatment consists of tetracycline (20-mg/kg-body weight given

daily by injection for 5 days). Be aware that reinfection is possible,

especially with asymptotic carries in the herd. Treatment of the whole

herd with tetracycline all at once may help prevent a reinfection.

However, whole herd treatment success

is difficult to quantitate. The new PCR test may be our best tool to

accomplish this goal. A more logical approach may be to conduct herd tests

and treat only those animals suspected of being carriers - PCR positives.

Controlling the biting insects will also play a key role in preventing

eperythrozoonosis.

David E Anderson, DVM, MS

Diplomate, American College of Veterinary Surgeons

College of Veterinary Medicine

The Ohio State University

9-26-2006

M. haemolamae has been diagnosed in llamas and alpacas all over the

U.S., in Australia, Canada, and in the UK.

There are no epidemics in any particular part of the country. It is a

blood-borne infection, so if there is sharing of blood during breeding, it

could possibly be transmitted that way, but I doubt it is common. If there

is a positive animal in a herd, there is a reasonably good chance that

there will be other positive animals, based on our testing data, but I

wouldn't necessarily suggest testing them all. This is usually a

subclinical infection which means that the majority of infected animals

never show any clinical signs. I would probably recommend testing animals

that are poor doers, anemic, or possibly those that will be stressed, eg

by being transported. There is no particular frequency for testing. The

PCR test amplifies the organisms DNA- it's either there or it isn't, so

the test does not give a titer- only a positive or negative.

The disease does cross the placental barrier, but a

positive dam is not necessarily going to give birth to an affected cria.

Treating with tetracycline usually resolves the clinical signs if there

are any, but our studies indicate that it doesn't usually totally resolve

the infection. It just decreases the number of organisms to a very low

level. Checking a CBC post-treatment is not a bad idea, although some

animals take awhile for their PCV to return to normal, and in a very few

of them, it also stayed on the low side. Moderate iron supplementation may

help return the PCV to normal after treatment, but I can't say for sure

that it does, because we have not done any controlled studies to show

this. The infection probably does not, per se, affect a female's chance of

getting pregnant, but again, we haven't done a controlled study to test

this. I don't think a positive test should decrease the value of an alpaca

as long as she/he is otherwise healthy.

Dr. Susan Tornquist, DVM

Oregon

From Syndram's Suris Website

Mycoplasma

haemolama/Eperythrozoonosis (EPE)

The infection formerly known as Eperythrozoonosis (EPE) in Camelids has

recently been reclassified as Mycoplasma haemolama.

An eperythrozooan is a little bacterium that affects the red blood cells.

It actually sits on the red blood cells and the immune system sees this as

a problem and tries to eliminate them along with the red blood cells. This

can lead to severe anemia or mild or moderate anemia particularly in

animals that are stressed or immune compromised. This organism probably

does not kill alpacas by itself, but is more often a complicating factor

in other diseases. This was first discovered in camelids in the 1990’s and

they’re still in the research stage of finding facts, they still don't

know how it's transmitted. Blood smear tests were first used to detect

eperythrozooan but were very hard to clearly identify and it is difficult

to study a disease if you can't detect it. The PCR assay is more sensitive

than blood smear exam for diagnosis of M. haemolama.

PCR

stands for preliminary chain reaction. It's a way of amplifying the DNA

from a sample. In other words if it’s present in small quantities and you

amplify it, it makes it easier to detect. At this point as an alpaca

owner, there may not be much to do. If you have animals that aren't acting

normal, losing weight, seeming sick, you want to consider having a vet

check them out. Tetracycline is the treatment of choice, but what is

unclear is if the tetracycline actually makes the organism go away, or if

it doesn't just suppress the disease to undetectable levels. Then, if an

alpaca carrying low levels of the organism gets stressed by shipping or by

some other disease, the eperythrozoons can start multiplying again.

|

|

Return To Medical Index

|

Return To Llama Management |

Return To Shagbark Ridge Llamas |

|